|

| Unlike Western kilns, air at the firemouth is regulated by stuffing with wood and by maintaining deep ash beds, rather than by choking air with a door or by closing ports. |

|

Escaping persecution

Almost all Korean folk potters are Roman Catholic, their ancestors having been converted to this "new" religion with an egalitarian appeal for those so low in society they could not legally record any ancestry, nor even take a last name. Persecuted for their conversion, they fled to remote mountainous areas and took up pottery, using two of the few resources available--clay and wood. Remaining in remote areas to this day, these potters are devout, independent, and proud of their work. Yet their children leave for jobs in the cities, and folk potters under the age of 40 are rare.

"Their children leave for jobs inthe city, and folk potters under the age of 40 are rare."

We visited several folk potteries in central South Korea, near Chonju, guided by Professor Han Bong-Rim, a leader within nonfunctional contemporary ceramics in Korea. A professor in a country where professors are near gods, he talked warmly with these poor but proud potters. We later found he had produced a video on folk potters, "before they are gone," he said.

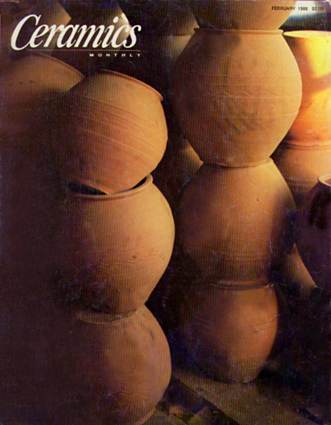

In Bu Chang Myun, a half hour's rough drive off a rural paved road, lies a pottery village founded as a sanctuary in 1888. A town of three large kilns and 100 people, it has its own school, and grows much of its own food. The main kiln, 105 feet long and 6 feet high inside, holds over 5000 ten-gallon crocks and is fired to hard earthenware temperature in seven days.

Lowering the firing temperature

In Whang San Myun, at a single-kiln pottery owned by Kim Hyun-Shick, the son of the previous owner, we watched a firing. Here, as at Bu Chang Myun, the traditional half-clay/half-ash glaze is fluxed with lead and manganese, lowering the firing temperatures from the hard stoneware range to the hard earthenware range. The lower temperature, along with the kiln's small size (70 feet long and holding1000 jars), allows a 36-hour firing. One potter expressed contempt for this new ware, unfavoraby comparing its shiny and crazed surface to the softness and depth of a nearby 40-year-old crock filled with pickles, but he readily admitted that lower labor and fuel costs were necessary for survival.

The future for "art potters" is brighter, because Koreans hold porcelains in high esteem. Calling themselves "traditional potters", they are in fact attempting to rediscover the technology of the celadons of the Koryo Dynasty (936-1392) as well as the white porcelains and slip-decorated stonewares of the Yi Dynasty (1392-1910). The rebirth of this tradition began in the late 1950s, after an almost 50-year hiatus that began with the annexation of Korea by Japan, and the subsequent destruction of the pottery industry by the occupation government.

"For old Korean potters, firing with wood is neither an artistic statement nor a statement about lifestyles, nor a romantic attempt to regain the purity of a less sullied past. "

We watched a firing at the nine-person pottery of Leem Hang-Teg in the Ichon Valley, the famed porcelain center near Seoul. Using pine, these potters fire their six-chamber, 300-cubic-foot kiln in 25-30 hours. Stoking is gentle, because even a speck of ash on a pot's glaze dooms it to the shard pile looming large near the kiln (even though trucked away once a year).

Beginning with a thoroughly modern touch, a cigarette lighter set a newspaper ablaze, which started the fire. Then the pig's head and rice wine offerings were brought out, with the latter being poured in the kiln. This ritual is standard for all types of kilns. Porcelain potteries may allow women to view the minute-long ceremony, but folk kilns, being more traditional, generally do not. We later ate the head and drank a few gallons of the same wine.

Another "traditional" pottery is fired in tube kilns to reproduce the unglazed stoneware of the Silla dynasty (57 B.C.-A.D. 936). When we arrived at the "Silla Pottery" of Yuo Hyo-Ung in Kyongiu, the old Silla capital, he was rebuilding one of the two side-by-side, 40-foot tube kilns on an ancient kiln site. Achieving a heavy reduction with a mixture of green and dry pine, he fires to 2370 degrees F (1300 degrees C). Yuo front stokes for six days and side stokes for one, slowly cooling to a dull red heat, and then quickly stuffs the kiln with green pine needles and seals it. The resulting ware is colored a wide range of grays, with little ash because the fuel is pine.

One last category of wood-fired kilns in Korea is a small tube kiln that produces earthenware as black as the wares of Oaxaca in southern Mexico. Chung Jin-Kook, a studio potter near Seoul, has two such smoke kilns. Instead of traditional rice steamers and roof tiles, Chung makes Silla-inspired wares and patio furniture. His kilns are fired in a day, and then, as in the Silla kilns, cooled to a dull red heat, stuffed with green pine needIes, and sealed.

An attitude toward process

Wood firing fits naturally into lives of Korean Potters. For them, firing with wood is neither an artistic statement nor a statement about lifestyles, nor a romantic attempt to regain the purity of a less sullied past. They wood fire because they have always done so. An integral part of their heritage, wood-burning tube kilns are viewed as ordinary, much as we Americans view our gas kilns.

In North America, wood kilns (usually the Japanese climbing kiln or the anagama) are exotic and often produce a mystical awe in observers and potters alike. Americans may even build tube kilns much as medieval Europeans built Gothic cathedrals, as glorifying monuments. Perhaps this is a necessary step in assimilating into American ceramics something so utterly foreign as firing a tube kiln.

"The future for "art potters" is brighter, because Koreans hold porcelains in high esteem. "

Here we are talking of an attitude toward process, not toward ware. Those looking for a genuinely natural attitude concerning process, the "real thing," must find the answer in a place and time free of the intellectualization provided by the tea ceremony aesthetic or artistic self-awareness. Perhaps they should look toward medieval Japanese farmer-potters or, more accessible, toward today's Korean makers of ong-gi (jars for kimchi), gentle old men who put pots into a kiln, put wood into it, and then take the pots out as naturally and unselfconsciously as they get up in the morning and go to bed at night. There is beauty in the gentleness and simplicity of their approach to this modest human endeavor, a gentleness and simplicity worthy of emulation. |